This is a post in my A Designer Learns Business series. I will continue to expand the series in the coming weeks and months.

When I previously wrote about designers up-skilling in business concepts, the intention was for designers to think about a company as a system. One can better understand the leverage points and the places where efforts can have outsized outcomes if one has a better understanding of the entire system..

At the risk of being too reductive, the best starting point is to think about how a company makes money and how it generates value. Input and output. There is a lot more nuance to it—the nuance is critical to truly understanding a business—but the following concepts are a great foundation from which we can both gain knowledge and begin investigating a new company. As we start to chart the money into the company and the value—which is not always money—out of a company, some patterns start to emerge. These patterns outline what we commonly think of as a business model.

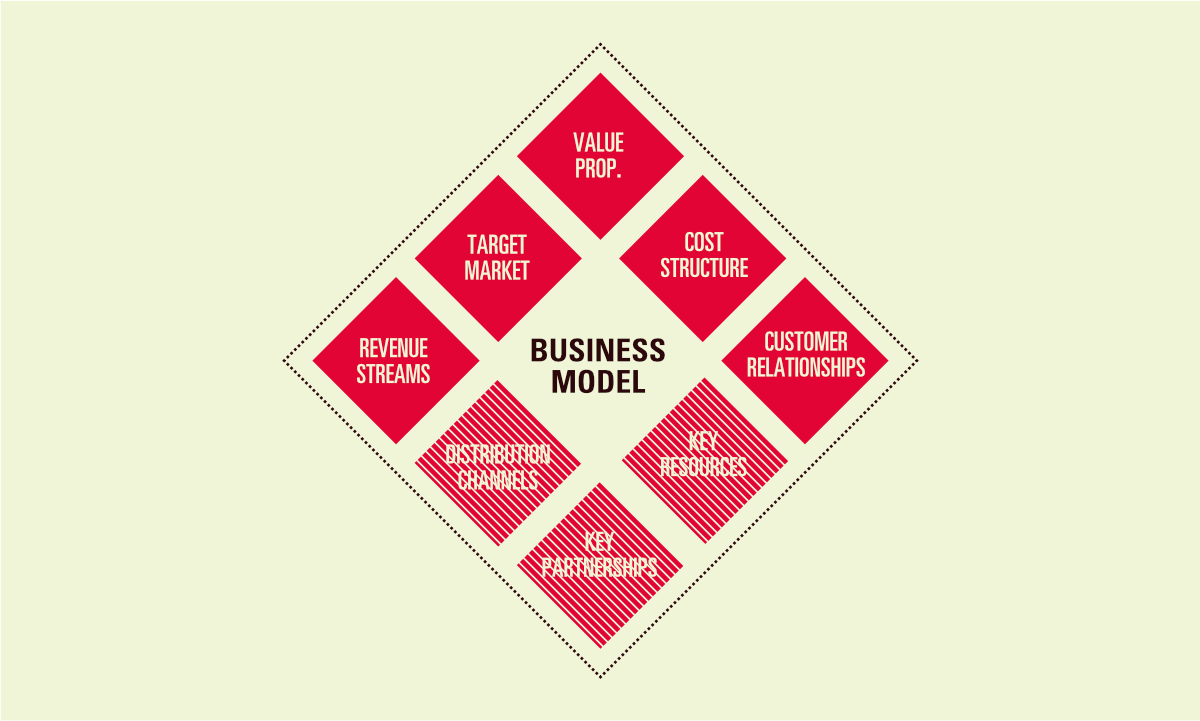

There are a handful of elements that make up a business model. For the purposes of design, I’m going to focus on the most relevant five elements:

- Value proposition

- Target market

- Customer relationships

- Revenue streams, and

- Cost structure.

Let’s break each one down through the lens of design.

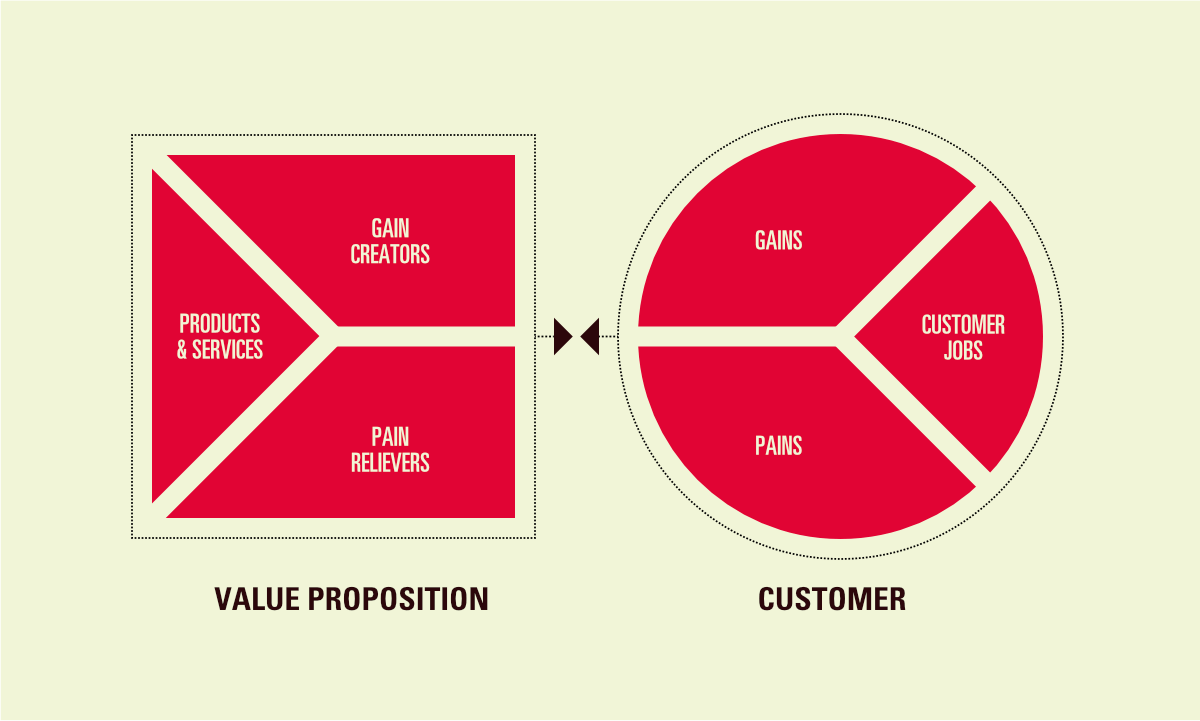

Value Proposition

The purpose of the value proposition is to clearly and succinctly communicate what pain points the business is solving for the customer, what gains the customer will receive, and what the product offering looks like. The value proposition should create clarity and alignment across the business by clearly stating the above. While this should ideally be very simple to communicate across a business, the value proposition (often “value prop”) can get murky for large and complicated businesses that have many business units and diverse venue streams. It may make sense to have a value prop for each business unit or vertical within a business. Generally, the idea is that a value prop is internally facing for business, but could be easily tailored for different external audiences.

High-level leadership should be the ones to set the value proposition for an organization because it touches every part of the business. Rarely is the value prop contained in a single artifact explicitly called a “value proposition,” but instead manifests in things like a company’s mission, vision, or strategic goals. The value prop should be widely circulated and easily understood. If a company lacks a value prop, things are very wrong, but it’s not the designer’s role to establish one. Instead, design leaders should ensure that their company delivers on their value prop.

It can be easy to stray from the original value prop of a company in favor of another enticing opportunity. In that case, it’s up to leadership to either reset the value prop or correct the deviation. Failing to do so results in a company in conflict with itself.

Target Market / Target Customers

The relevance of a defined target market or customer should be immediately apparent for designers: these are the people—or groups of people—that we are designing for. However, one essential point is the frequent disconnect of an intended or aspirational market/customer from the actual market/customer.

Designers are often brought into projects to uncover actionable insights about customers or to identify whether a business is reaching its targets or not. This work can be done in partnership with market research efforts to provide a more comprehensive picture of customers.

Target market and customer models can be particularly fraught with assumptions at every level of a company. And while there may be some element of truth to a coworker or leader’s conception of customers, it can be perilous to take these assumptions at face value. “We know about our customers,” can be a dangerous statement because markets are always in flux and what may have been true in the past may not be true tomorrow.

Designers must also challenge collaborators and business leaders to expand their conceptions of target markets and customers beyond demographics. In almost all cases, the reason why a person chooses a particular product has nothing to do with their income or geographical location. Uncovering the real “why” of a buying decision requires that the team must dig deeper. More useful profiles of markets and customers include additional dimensions such as psychographics and behavioral traits, as well as common needs or pain points. These elements are frequently determining factors for product adoption and engagement. As such, they should not be overlooked, but instead sought out through deep research.

Customer Relationships

This is where things start to get a little squishy. Customer relationships are critical for designers to understand to influence them. A greater understanding of these relationships can identify issues with your sales funnel or uncover opportunities for product growth.

Broadly speaking, a customer relationship is how a business interacts with its customers. This could be how a business acquires new customers, how they make themselves visible to new customers, what types of transactions a business encourages, and what type of cadence or duration those interactions happen in.

For those with a holistic experience design approach or a background in service design, this has a clear relevance for designers. While customer relationships aren’t often set at the leadership level, relationship goals might be. For example, it may be a company goal to increase the top of a funnel, so it should be important for a designer to understand how the business could do that.

A common organizational desire is to change the quality of a customer relationship to another more advantageous state. For example, current customers may interact with a business in a transactional nature and only when something is needed. This creates opportunities for competitors to step in and fosters very low brand affinity. One could see the value in altering the customer relationship to foster a deeper connection with the business.

There are many ways to achieve a change in a particular customer relationship, which is where design practitioners can come into the equation through concept exploration, discovery activities, or any other applicable method. This is why it’s essential for designers to both understand a business’ customers as well as how they relate to the business.

Revenue streams

I hope that we’re at the point where I don’t have to dig into the importance of knowing how a business makes money. What may be less important is understanding all of the sources of business revenue.

A great example is Google, which you might think of as being in the business of providing software like Gmail, the Android OS, or the Workspace suite. In fact their greatest source of revenue is selling advertising, primarily served to people using their search engine (but also YouTube and in-app ads). In 2023, Google generated 237.85B from ads across their platform, or approximately 77% of their total revenue. Every other product that they make generates significantly less revenue, if any at all. If you were a designer at Google working on a product that serves ads, any design decision that would jeopardize their advertising revenue would be highly scrutinized and weighed against trade-offs.

In the context of design, knowing where the money comes from is critical. You, as a designer, will need to make money for your company. If you’re not working on something that makes money for your company, your job is more at risk. Unfortunately, it’s as simple as that.

The clearer that you can draw a line from the work you do and the value that it generates for the business, the more resilient you will be in your role. If that line is currently a curvy, convoluted, gnarled line, do whatever you can reasonably do to get closer to value by making changes to your role.

Consider what stage your company is in and where your leadership is focused. While reductive and oversimplified, most businesses are primarily working to achieve one of two things: growing revenue or reducing cost.

To grow revenue, a business needs to expand their relationships with existing customers or find new customers. This is an area where designers—with our skills in customer research, ideation, discovery, and validation—are positioned to succeed.

The most secure position for a designer to be is tasked with growing the revenue of an existing product. Your company has established the viability of a product or service but also identified (possibly through design activities) that there is a new opportunity to general additional income. This is a fantastic place to be as it requires minimal new resource investment from the business as well as the low-risk bet of starting with a proven winner.

If, instead, you’re in the position of having a role that is tasked with finding entirely new sources of revenue, you’re likely in a precarious spot. Especially in difficult economic times, leadership tends to cut initiatives like these and lean into optimizing existing revenue streams. While these are arguably short-sighted cuts, they are a sad reality. If this relates to you, do whatever you can to hedge your bets. Go back to basics starting with the value prop, or ensure that you have a fallback if the rug gets pulled out from under you.

Reducing operational cost is not going to be an effective use of designers, though they may be especially good at it. Design is a cost center (more on this later) and spending the money to fix small things is rarely worth the investment of staffing projects with designers. If you find yourself in this situation, know that your role will be in jeopardy soon. Reducing cost centers is often the first move in any period of economic hardship or when a company wants to appear more profitable than it actually is (e.g., before an IPO or acquisition).

Cost structure

Design is—and always will be—a cost center. Cost centers are functions that take business resources (i.e., money) without directly generating revenue. This makes every design role more precarious than it would seem, and why design roles are often on the chopping block with the first round of layoffs. This is painful, and not an easy truth to reckon with. As I mentioned in my other post, I’ve felt this more times than I care to revisit.

Knowing where the business incurs costs is valuable for design work. Any solution should take into account the explicit or implied costs. There will be the cost of an engineer’s time to build, test, and deploy any new code. Potentially there might be some costs to message and market product changes. What about customer support? Triaging any issues that might come up with the changes? Will it impact processes in the physical space such as retail? Are there revenue or legal ramifications to the changes that you’re proposing? There is no scenario where a business operates without costs, but figuring out which costs are acceptable and which are not is the hard work that designers need to do. The importance of these considerations cannot be overstated.

In these scenarios, the best thing a designer can do is to model out various outcomes. If you are unsure of how to make the case to change an experience, start with a list of costs and model those out to a reasonable time horizon. Balance those with any potential net benefit (see previous section). If you’re in a particularly advantageous position, you may be able to leverage data science peers to improve your models. This activity will put you in the ideal place to argue for—or against—the case of taking action.

Wrap-up

I hope that I’ve given you a starting point to start digging into the inner workings of your company. I can appreciate that this info is a lot, even though I’ve only scratched the surface on some of these topics. At this point, I’m trying to lay the groundwork on how to put some of this info into practice. We’ll continue to build on it in subsequent posts.

My challenge to you at this point is to remain curious. If you can dig into some of the gaps in your understanding of the business, so much the better. It will inform your design work on some level and make you a better designer.

I have plans to expand this series and continue to give designers more tools to be fluent in business concepts. If you’ve read this far, I’d be interested in any feedback that you might have. Feel free to drop me a line on Mastodon or LinkedIn.

Postscript: I would like to thank Marc Amos, Eric Bailey, and Joe Martucci for their help in editing this post. They helped me polish my mad ravings into something human-readable.

No Comments.